Objects of WarThe late second millennium saw a number of wars that occurred on a global stage.

Conflict, by its nature, leads to considerable innovation, and each object here showcases a gifted inventor working to make life more convenient, efficacious and all-round more straightforward for soldiers on the battlefield.

Object Title: Bandage and wrapper C. 1940 AD White rayon with adhesive, plastic

This piece of absorbent fabric is similar to others found in archaeological digs across the country which almost always have stains of blood in one concentrated spot in the centre - though this one appears to be untainted.

This wealth of archaeological evidence clearly shows these types of fabric were used as bandages, probably for small wounds such as ones caused by darts as seen in object (2). The other side of the object has a weak adhesive to affix the bandage in place under clothes. These types of bandage are usually stored inside a plastic wrapper to keep the equipment sterile. Bandage wrappers tend to sport bright colours so that they could be easily spotted in a crowded medical kit.-

A disposable menstrual pad. The adhesive holds the pad to the underwear.

Object Title: Goblet C.1910- 1920 AD

Plastic

Traces of blood were found on this goblet so it was likely used to drink the blood of the owner’s enemies as a symbol of victory in battle. It is made of a type of pliable plastic, presumably so that it can be transported the long distances required for war without the risk of breakage. The loop at the bottom, which once had the goblet’s stem and base attached, was used to string the goblet around the neck of the owner to symbolise his fierce battle skills. There likely would have been a separate base on which to stand it.-

Menstrual cups are a reusable menstrual product, worn in the vagina to collect menstrual blood.

Dynarex, Super Plus Tampons Cardboard Applicator

Object Title: Blow pipe C. 1945 AD Cardboard

Acquired by Major Horace Millington while serving in the Battle of Farmworth Beach, this blowpipe is the highlight of the Museum of Mankind’s collection. In a letter to the Museum’s original curator, Sir Ernest Claymore, it is said the artefact was discovered deep in the sand while digging trenches. The tapered end of the blowpipe would ensure the poisoned dart would not accidentally slip back into the user’s mouth, and the width is perfectly sized to ensure a tight seal around the lips.-

Some people prefer to use an applicator to help insert their tampons.

The Default MaleThe Single Sex Model

The teachings of Galen, a 2nd Century physician, have formed the basis of western medicine for almost 1500 years. He believed that men and women had the same body parts but were different in the fact that men’s bodies were hotter and women’s bodies were cooler. This heat caused the penis to be pushed out of the body. If it was not hot enough, the organ would stay inside and become a vagina.

This explanation of the difference in the sexes was useful to society as it provided a seemingly legitimate reason to treat women as inferior citizens and bar them from certain parts of society- women simply weren’t developed enough in the eyes of society to be trusted with anything of importance. This idea of women’s ‘innate inferiority’ has seeped into museums in a number of ways, even after the science of sex differences were later updated

“Turn outward the woman’s, turn inward, so to speak, and fold double the man’s and you will find the same in both in every respect”

-Galen

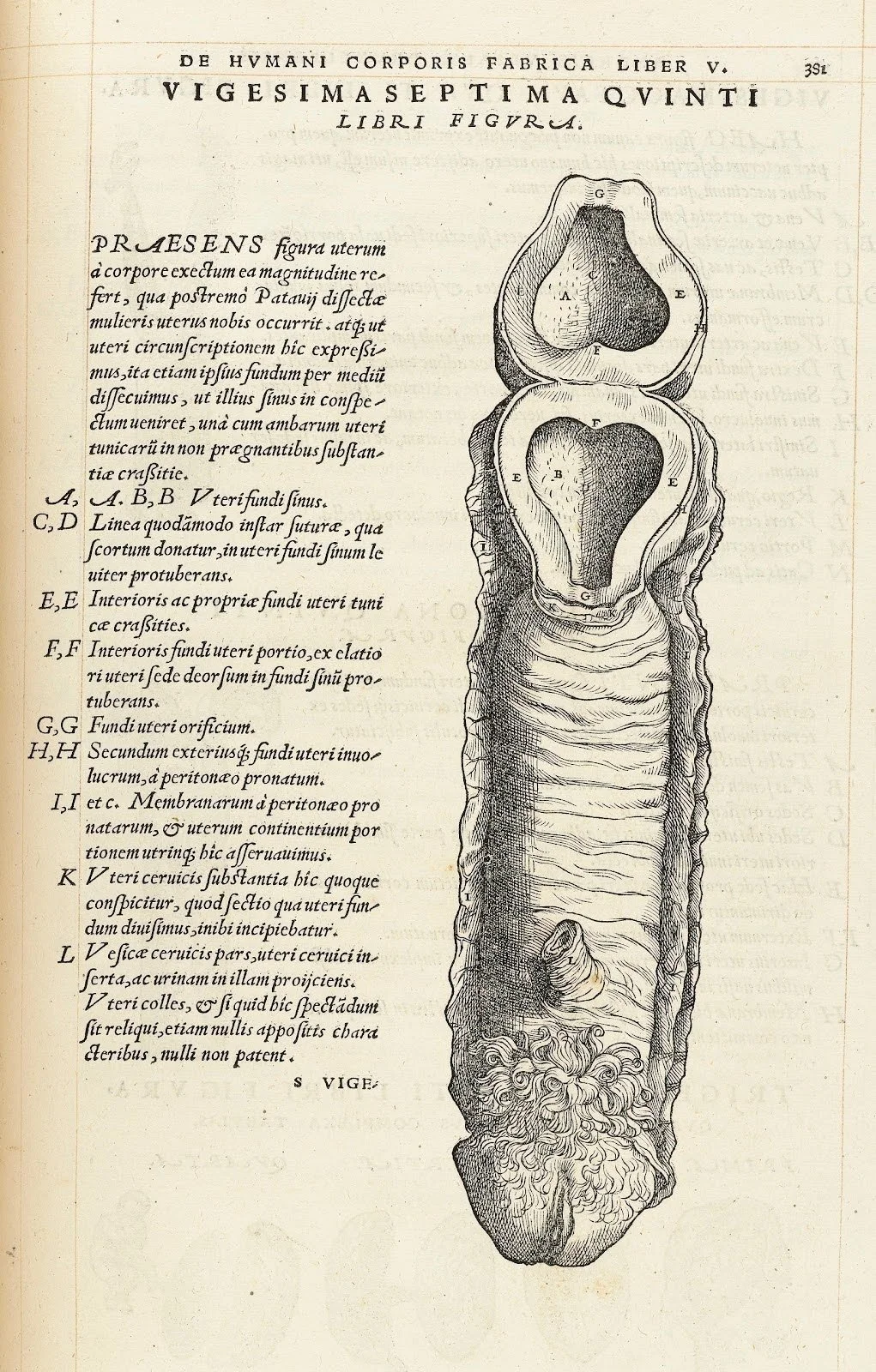

The anatomy of the vagina , which was believed to be an inverted penis at the time. This image is not remotely anatomically correct. Vesalius also believed that the clitoris was a pathological structure which did not exist in healthy women. This is also not anatomically correct.

Illustration from the anatomy book “De humani corporis fabrica” by Andreas Vesalius published in 1543 showing the anatomy of the vagina, which was believed at the time to be an inverted penis.

Image: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Androcentrism

Androcentrism is a bias - conscious or subconscious - placing a masculine point of view at the centre. Men are regarded as “default” and women are a deviation, special, or different.

This view is represented in museums in subtle ways, such as assuming objects were used by men for traditionally “male” activities like war, even though there might be little evidence to support this claim.

The idea that women were “underdeveloped” men has appeared in writings since antiquity and persisted into the 19th century.

Natural history museums, science museums and anthropology museums often have a ‘tree of life’ or the famous illustration ‘March of Progress’ showing the path of hominid evolution. Humans are often represented with a typically masculine body.

March of Progress poster displayed at Lucknow Zoo, Sumit Kumar Singh, 2016

In Object for Men

When objects are found in archaeological digs or purchased by a museum without context or provenance, it is often assumed they were used by men unless they fit modern standards of gender roles and stereotypes - standards that may not have existed in previous societies.

In the 1950s in modern day Democratic Republic of Congo, then a colony of Belgium, a Belgian archaeologist Jean de Heinzelin de Braucourt discovered a 25,000 year old bone with notches carved into it. Called the ‘Ishango bone’, the notches were clearly made deliberately, in groups of around 30 marks. Many papers have been written asserting various theories, including the bone was a method of record keeping, possibly counting livestock; proof that the ancient people counted in base 12; a way of recording prime numbers; or they track lunar months.

30 years after the bone was discovered, ethnomathematician Claudia Zaslavsky proposed that the bone may have been used as a menstrual tracker by someone who wanted to keep track of their periods.

The Ishango bone on display at Institut Royal des sciences naturelles de Belgique, Brussels 2007

Notches on the Ishango bone, Albertils