What is endometriosis?

Endometriosis is when cells similar to ones in the lining of the womb, also known as the endometrium, grow somewhere that isn’t the inside of the uterus.

Just like endometrial cells, those cells respond to hormones by growing and sometimes even bleeding, just like a period. Unlike in the uterus, there’s no way for the cells and blood to escape, so it stays trapped, causing lumps, pain, inflammation and scarring.

Usually, endometriosis is found growing in the pelvis, pelvic lining, the ovaries, the bowel and the bladder. But up to 10% of people with the disease have it outside the pelvis, as far reaching as the lungs or brain.

It affects 10% of people assigned female at birth - but there may be even more as there are so many barriers to diagnosis.

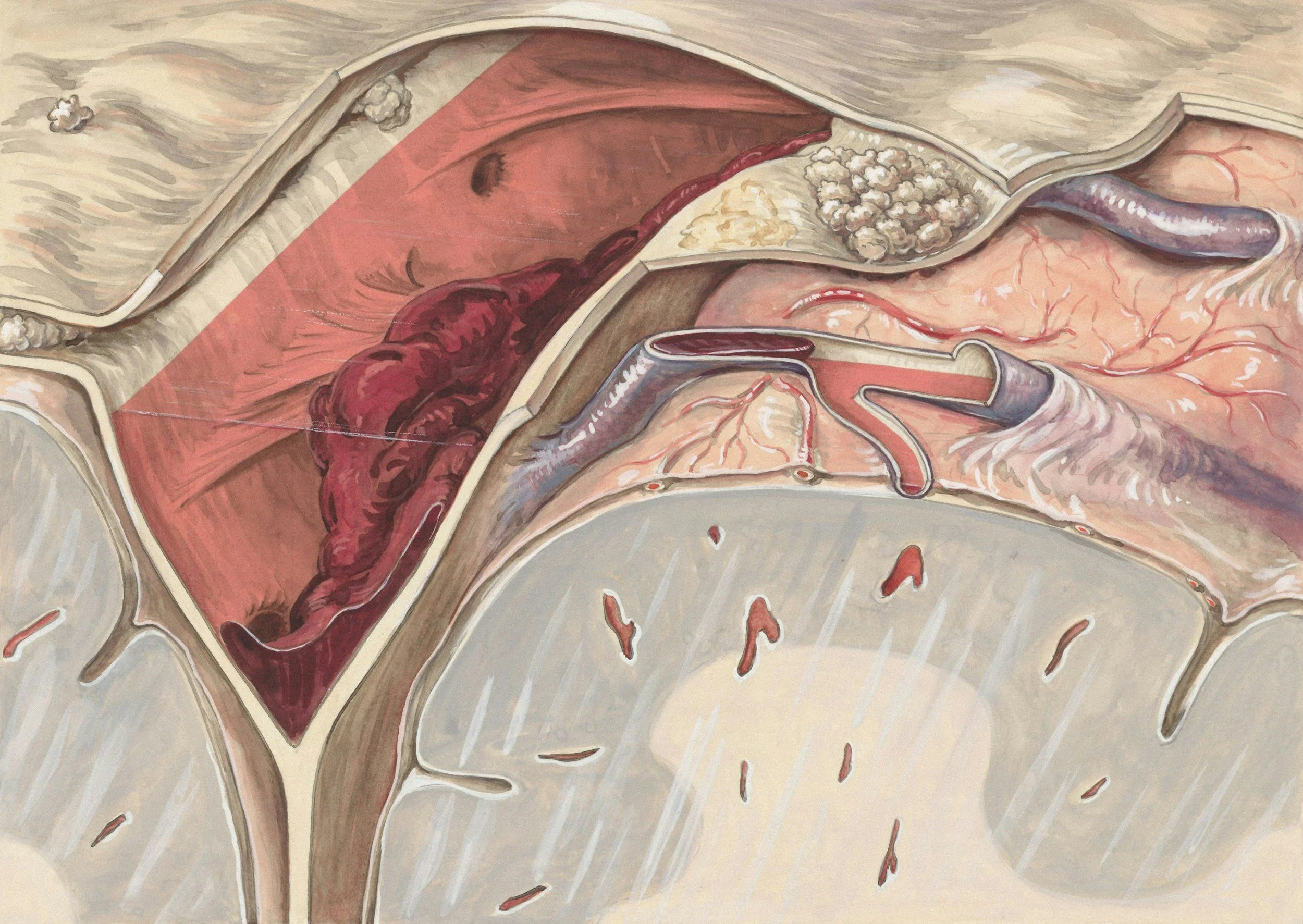

Diagram of Endometriosis, NHS.

Available at: www.nhs.uk/ conditions/ endometriosis/

What is the cause?

The cause of endometriosis is currently unknown. It’s likely a combination of factors. Theories include genetics, environmental factors, menstrual blood flowing in the wrong direction up the ovarian tubes, a bacterial infection, or cells changing type - for example, a lung cell into an endometrial cell.

Symptoms

Heavy menstrual bleeding

Fatigure

Chronic pelvic pain

Bleeding between periods

Extreme period pain

Bloating

Depression

Anxiety

Nausea

Pain when going to the toilet

Chronic pain outside the pelvis

Symptoms don’t always correlate to how much endometriosis there is or where it is found. People with endometriosis are also more likely to have other immune and chronic pain conditions, which means sometimes it’s difficult to say what exactly is causing the symptoms.

Does everyone have the same symptoms?

Symptoms vary from person to person and it’s currently unclear why. 20–25% of people with endometriosis have “silent endometriosis”. In these cases, there are few or no symptoms and it is only discovered if that person is having difficulty getting pregnant or having surgery for something unrelated.

This short film was written and directed by Bonnie MacRae inspired by her experiences with endometriosis. It was made by an all female and non-binary crew and filmed in Glasgow.

The film examines contradictions and correlations: comparing the pain of chronic illness with the pain of medical gaslighting, and contrasting the joys and challenges of coming of age while working class and disabled. It explores cycles that reflect the menstrual cycle - the repeated doctor’s visits are set to a repetitive, frenetic soundtrack.

Shown with permission from the director.

All Up There

Into the Unknown: Your Experiences

“The first extreme pain I remember was Boxing Day in 2011. I recall the date so clearly because after being admitted to hospital and given morphine to ease the pain, a male doctor remarked that I probably “ate too much on Christmas” and sent me home.”

“After living with insane pain for a year and finally being listened to, it was a relief to have a doctor believe me.”

“Growing up in India questioning why can’t I enter temples while being in severe pain at the same time, just felt wrong and created self doubt.”

“I left work one day with a sharp pain in my pelvis. I went to the ER twice in a couple days. They didn’t see anything wrong with me. I was told I was just “backed up” and to try an enema. I was told it was anxiety. I was refused painkillers and was told to go home. ”

“Doctors and family and friends telling you, “you don’t look sick” makes me cringe every time I hear it. I tell myself I am stronger than this disease and fight every damn day!”

“Doctors told me it was just a period. I would pass out, vomit and collapse. “Just take a paracetamol,” they would say.”

“I once passed out in the toilets of a McDonald’s at the age of fifteen and people thought I was on drugs.”

“I remember being in the bathroom at home, hugging the toilet while trying not to vomit from pain. My dad banged on the door, shouting at me to “either get over it, or go to the doctor”. I couldn’t go to the doctor. We didn’t have health insurance.”

“I have since found out 2 of my aunts have had hysterectomies in their 30s due to similar issues and cysts. I found this out at 40! Imagine how I might have approached my fertility had I known this was in my family history, I certainly wouldn’t have waited till I was 40. Why don’t we talk about it, why don’t we share our fights?”

“It was a lightbulb moment when a friend was talking about another mutual friend’s struggle with the condition: “Wait a moment – that sounds like me!””

“The best of this situation: after my diagnosis, a lot of friends, colleagues and women around me (more than I ever thought) shared with me their experiences with endometriosis, this made me feel less alone, but also made me become aware of how long we still have to go.”

Myth Busting

Endometriosis isn’t cured by getting pregnant:

There may be a brief reprieve of symptoms during pregnancy, but they may return once the menstrual cycle starts up again. A common symptom is infertility, so this myth is particularly harmful.

You can get it at any age:

Teenagers can get endometriosis. The idea that it doesn’t start until your 20s or 30s is likely due to the long time it takes to get a diagnosis.

Hysterectomy isn’t a cure:

Because endometriosis occurs outside the uterus, removing the uterus may not cure it.The pill isn’t a cure:

The pill may reduce symptoms but it won’t get rid of endometriosis.

It’s not just white women who get endometriosis:

Because endometriosis has historically been believed to be more common in wealthy women stressed by ‘modern life’, it was assumed to be more common in white women. However, studies show Asian women are most likely to be diagnosed with the disease. It is unclear exactly if racial disparities exist due to how difficult it is to get a diagnosis. The idea that it was a white woman’s disease was a useful tool for white supremacy to engage in eugenics and attempt to control the birth rate by pressuring white women into having more children.

Endometriosis doesn't stop at menopause:

Menopause doesn’t necessarily mean the end of symptoms. The scarring and inflammation from years of this chronic illness may have long-lasting effects on the body. But symptoms usually lessen after menopause. Sometimes the disease can happen after menopause - about 2.5% of patients are postmenopausal. This usually happens as a result of HRT. How HRT affects patients who already have endometriosis is unclear.Endometriosis is not a “career women’s disease”:

It used to be believed that endometriosis was most prevalent in women who didn’t have children or had children later in life. This was a convenient way to pressure women into having children earlier, deny access to contraception and discourage them from advancing in their careers and financial independence.

It's not only cis women who get endometriosis:

Anyone born with a uterus can get endometriosis - that includes trans men, non binary people and intersex people. There are even cases of cis men and people with penises having endometriosis.

Endometriosis in history

Signs and symptoms of endometriosis have been observed for thousands of years.

Ancient Greek physician Hippocrates (c. 460 - c. 370 BCE) wrote about adhesions on the uterus. But it wasn’t until 1860 that endometrial tissue outside the uterus was identified by Austrian physician Baron Carl von Rokitansky (1804 - 1878). In the 1920s, American gynaecologist John A. Sampson (1873 - 1946) coined the term ‘endometriosis’.

Endometriosis, however, is part of a much larger narrative of how society imagines our bodies - as vehicles for wombs that must be controlled by society.

Nowadays, we see the legacy of the wandering womb and hysteria in endometriosis. From the myths that it can be cured with pregnancy or hysterectomy, to the misdiagnoses of chest pain from thoracic endometriosis as “anxiety”, patriarchal myths of how women’s bodies should conform persist.

In ancient Europe and the Middle East til at least the 1600s, it was believed that the womb was an independent animal that if left idle would travel around the body.

Any symptom a woman had could be explained this way: chest pain? womb’s there. Short of breath? Womb’s in the throat. Madness? It’s got in the brain.

The first line of treatment would be pregnancy which would weigh the womb down and bring it back into place. Another treatment was “womb fumigation”, which has since been rebranded as “yoni steaming”.

Image: A midwife administering womb fumigation to promote fertility.

Illustration from The ten pleasures for marriage and the second part the confession of the married couple, 1682, attributed to Aphra Benn. Public domain.

Hysteria

Wandering womb evolved into the disease known as “hysteria”.

The origin of the word is from the Ancient Greek for womb: hystera. Hysteria was a vague disease with symptoms as wide ranging as abdominal pain to excessive emotions.

Treatments included admission to an asylum and hysterectomy. Hysteria was a convenient diagnosis for any woman deemed “difficult” and was a way the patriarchy exerted control.

Illustration from Hysteria and Certain Allied Conditions, 1897, by George J. Preston M.D. Public domain.